In the slums of 1830s London, coming across the token scavengers, costermongers, pickpockets, street Arabs, and prostitutes was part and parcel of living in a metropolis so densely populated and increasingly divided. Thanks to ethnographies such as Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, racialization and hasty dismissal of the lowly slum-goers became the norm, as these unsettled and physically demarcated “wanderers” floated around their cramped abodes showcasing vice rather than virtue.

A lovely image, right?

However, characters such as Nancy in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist throw a bloody important wrench in this societal set-up of us vs. them. A prostitute (who, by the by, is never actually called a “prostitute” in the novel, we’re just left to conclude that she is via description and living conditions) who falls in line with Sikes’s and Fagin’s gang of miscreants, Nancy emerges as the tragic heroine whose ill-fated bravery saves Oliver from a life of squalor.

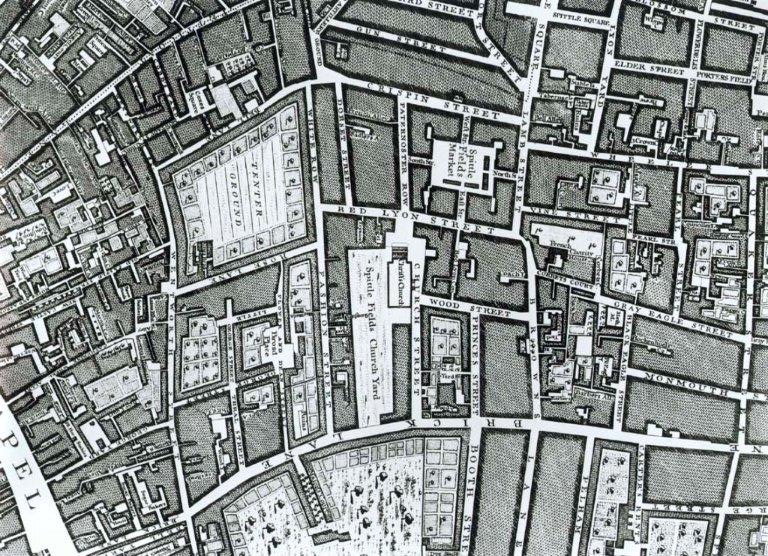

Once she learns of Monks’s evils plans for young Oliver, an alarmed Nancy devised the plan to drug Sikes with laudanum and make her way over to Rose and Mrs. Maylie in order to reveal the truth behind Oliver’s return to Fagin. Although “[t]he girl’s life had been squandered in the streets, and the most noisome of the stews and dens of London,” she still had “something of the woman’s original nature left in her still … [and] one feeble gleam of the womanly feeling which she thought a weakness, but which alone connected her with that humanity, of which her wasting life obliterated all outward traces when a very child” (332-333). Keeping with the Victorian ideal of woman as a gentle domestic angel, this insight into Nancy’s sensitive nature interrogates the detached Mayhew-ian categorization of destitute Londoners. Nancy, fueled by a desire to seek justice for Oliver, takes the initiative to leave the rookery of Spitalfields “towards the West-End of London,” despite the threat to her safety if Sikes were to discover her actions (330).

A zoomed-in map of Spitalfields

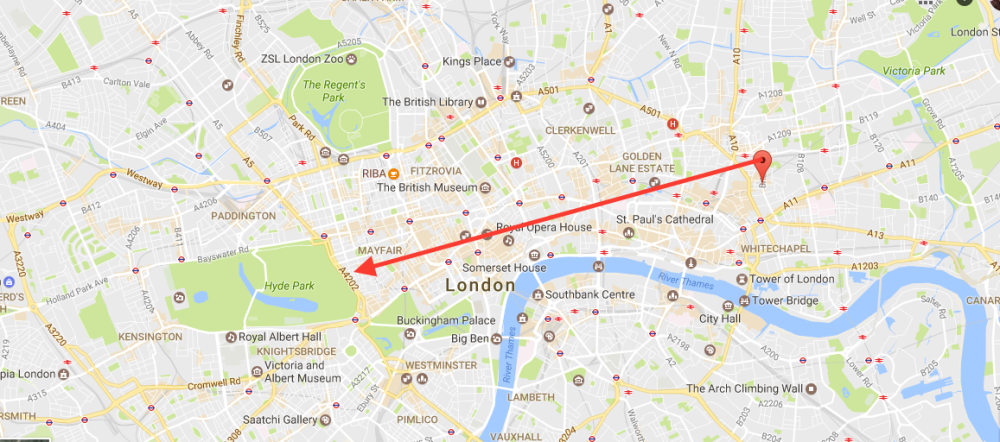

While Nancy experiences an internal shift from passive to morally active heroine, she also undertakes a physical movement from the East to the West of London (a.k.a. slums to very-not-slums). The narrator notes, “[w]hen she reached the more wealthy quarter of the town, the streets were comparatively deserted, and here her headlong progress seemed to excite a greater curiosity in the stragglers whom she hurried past” (330). This quick yet poignant remark on how the streets are considerably less congested the more west you travel underscores the shift in anonymity that Nancy undergoes. While still rushing through the East-End streets, she had to navigate through “the narrow pavement, elbowing passengers from side to side and darting almost under the horses’ heads, crossed crowded streets, where clusters of persons” were found. While just another young unindividuated prostitute in the polluted streets of the Spitalfields area, Nancy emerges as noticeably distinct figure when she traverses the road less travelled by by those among her kind. However, this ability of hers to stand out in such an area is tainted by her lowly status, for the “curiosity” shown by wealthier Londoners manifests itself into “chaste wrath” seen “in the bosoms of four housemaids, who remarked with great fervour that the creature was a disgrace to her sex, and strongly advocated her being thrown ruthlessly into the kennel” (331). Although not affluent themselves, the housemaids waiting on the Maylies at “a family hotel in a quiet but handsome street near Hyde Park” still demonstrate a critical view of anyone who resides in the *gasp* slums. The fact that the animalistic image of throwing Nancy into a “kennel,” for she is a disgraceful “creature,” also augments the view of slum-goers as distasteful mongrels. That Nancy herself neglects to give her name but instead calls herself a “creature” when speaking to Rose emphasizes how belittled and inhumane Nancy’s lifestyle has made her feel. What’s also important to note here is that Nancy in now located near Hyde Park when these phrases are uttered, a wealthy area embedded well into the City. The “quiet but handsome street” on which the Maylies are staying is certainly nowhere to be found in the grimy Spitalfields that Nancy temporarily leaves behind.

A modern-day Google map of London showing a general direction from Spitalfields to Hyde Park (East to West, which, circa Oliver Twist, was a no-no direction for individuals to go)

In addition to the spatial transitions that Nancy makes from East to West, the temporal stasis that marks her movements further reveals how trapped Nancy is in the world of the fallen woman. By day, she continues with the charade of loyal Sikes-Fagin gang member (granted, her facade cracks almost enough for her to blow her cover), but by night, Nancy turns into the active heroine who abandons her comfort zone for Oliver’s sake. That Nancy undertakes this endeavor of justice under cover of nightfall echoes the expected activity of the prostitute as an evening streetwalker, but does so in a contrasting way: Nancy is not navigating the streets at night in an effort to continue her life of vice, but rather utilizes night as a tool to do good. Her awareness that her presence in the West-End during the day would be downright unacceptable (and considerably more difficult to achieve under Sikes’s eye) instead of merely surprising reflects the caution with which Nancy develops her strategy. Moreover, that she tells Rose “[e]very Sunday night, from eleven until the clock strikes twelve … I will walk on London Bridge if I am alive” further speaks to the usage of time as an asset (337). She has chosen a “settled period” for her presence to be made, challenging the Mayhewian idea of settled vs. non-settled as belonging to us vs. them (337). Nancy, a member of “them” uses London Bridge to literally bridge the gap between the two sectors of London, thereby demonstrating a sort of rebellion against the crude division. London Bridge itself connects North London to South (from Middlesex to Surrey), connecting a non-slum to a land to which more and more of “them” were being relocated as an effort to purge the North and West of London.

London Bridge in the 1830s

Although Nancy ultimately returns to Sikes and meets a tragic demise, her ability to breach geographic and social divides demonstrates the complexity of her character and the subversion of crass Londoner stereotypes.

https://aplaceofpossibilitea.wordpress.com/maps/